The Fed’s LIBOR Tools. Add Tacit Complicity?

The LIBOR Problem

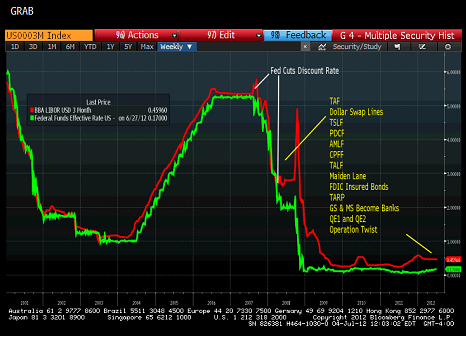

During the Financial Crisis, the Fed, the Treasury, and the FDIC were all fighting to keep the banks solvent. They all wanted banks to have access to cheap funds. The market became focused on LIBOR (and CDS) as a key indicator of the health of a bank. High LIBOR submissions were taken as a cue that the bank was in trouble. This in turn meant that the regulators focused on it.

The regulators wanted to make sure the banks were solvent and that the market knew it. Since they couldn’t control LIBOR directly they took other steps. Program after program was implemented to reduce the cost of bank borrowing, but in the end, LIBOR remained high because the availability of cheap funds from a central bank wasn’t the same as good and equal credit quality.

Let’s run through a list of steps and actions that were taken during the financial crisis to try and reduce bank borrowing costs.

Fed Funds Target Rate

The primary tool had always been the Fed Funds target rate. LIBOR traditionally traded at a premium to that. The premium was relatively stable because the LIBOR panel banks were all high quality and had very low credit risk, at least for short dated loans. So if the Fed wanted to affect what rate banks lent to each other at, all they had to do was lower the Fed Funds rate.

This started to break down in 2007 and by 2008 LIBOR was being set at levels that were nowhere close to the Fed Funds rate. So the main policy tool the Fed could use to lower bank financing rates had failed.

The Discount Window

For my entire career, any bank that was rumored to have used the discount window was immediately viewed as being in trouble. Borrowing from the Fed at the discount window was tantamount to admitting that you had totally misjudged your funding needs. It carried a negative stigma in addition to a premium cost.

But the Fed tried to change that. They reduced the rate for borrowing at the discount window and in fact encouraged banks to use it. It was a big deal when banks “tested” the system. The Fed wanted the world to know that banks could borrow from them at the discount window and it wasn’t a bad thing. That too ultimately wasn’t enough to get banks to lend to each other.

Central Bank “Swap” Lines

The Fed can only help U.S. banks. It can’t directly lend to foreign banks, so global “swap” lines were created. The Fed could lend to the ECB or BOE in dollars who would in turn provide dollars to their banks. These lines were put in place so that British banks could turn to the BoE for support, not just in British Pounds, but also in dollars. This too ultimately failed to encourage banks to lend to each other.

Term Auction Facility

The first attempt to directly affect longer term rates (rather than overnight) was the creation of the Term Auction Facility. TAF allowed the Federal Reserve to provide collateralized funding for terms as long as 84 days. This was seen as a way of ensuring banks had capital for longer periods of time. This program was also meant to improve credit spreads in the secondary market for corporate bonds and mortgage backed securities. The Fed seemed to believe investors weren’t buying these assets because of a liquidity problem. The reality was people weren’t buying these assets because they were scared of the credit. Just like Europe has done, the Fed mistook real credit concerns as problems with liquidity. This program failed to help banks or the various credit markets.

Bear Stearns

The Fed was clearly involved in JPM’s purchase of Bear Stearns because not only did the Fed finance a portion of the worst positions on Bear Stearns’ books, but the Fed took second loss risk. This was unprecedented. Not only was the Fed letting JPM take some Bear Stearns assets off their books, not only was the Fed going to fund those assets, but JPM’s losses on those assets were capped. This again was a sign of how far the Fed was willing to go, and it did work for awhile. Credit fears did decrease when this occurred.

AIG

The AIG bailout was really a bailout of the banks that had bought CDS from AIG. This was the Treasury department at work rather than the Fed, but the intention here was to help the banks. If AIG FP went bankrupt and AIG the parent then followed suit (the insurance entity was separate) then the banks would have been out of a lot of money. GS, in particular, claims that they had protection against that, but clearly the regulators and the markets were concerned about a possible daisy chain of defaults. The amount AIG owed as collateral was staggering (we will ignore that the Treasury locked taxpayers into losses right near the bottom). This deal was done to protect not just the credit spreads of some of the banks, but the outright solvency. It kept them solvent, but still didn’t make the banks lend to each other.

FDIC Limits and FDIC Bonds

The FDIC increased limits on how much was covered for any account. The FDIC was doing its part by ensuring that depositors would stay at banks. They also allowed banks to issue bonds with an FDIC guarantee. That helped banks to borrow from the “markets” again at much lower rates than where their unsecured debt was trading. But that’s all it did. It gave banks yet more ways to get cheap funding, but it didn’t translate into bank unsecured credit spreads doing materially better, and wasn’t helping banks lend to each other, which is what LIBOR needed.

Goldman Sachs and Morgan Stanley Become Banks

GS and MS were invited into the banking fold. As concern mounted that these two institutions, key parts of the web of derivative trades, would have funding difficulties, they were given banking licenses so that they too could enjoy cheap Fed money. It was designed to reduce the systematic risk of the derivatives markets and to prevent another potential collapse that now obviously could lead to yet another one. So this was done as much to protect the banks as to protect these two companies. Again, it didn’t help encourage banks to lend to each other in a way that would help LIBOR.

Commercial Paper and Money Markets

Suddenly money market funds would be guaranteed. The fear was that as people pulled money out of money market funds, yet another source of bank liquidity would dry up. The commercial paper intervention is a bit trickier to follow. Companies who relied on commercial paper started to get very nervous that they wouldn’t be able to “roll” their CP, and they also got nervous that if they failed to roll their CP, the bank might not fulfill its commitments under their revolving credit agreements. So a stealth run started where companies were drawing down on their revolvers, “just to be safe”. That was putting more strain on the banks as they had to borrow money to fund those drawdowns. So the commercial paper market was also ripe for intervention, again to ease strain on bank funding.

TARP

What started as a program to buy assets from the banks turned into capital injections. This was a better step as it provided cushion for the creditors, but yet again failed to encourage banks to lend to each other.

TALF, QE, ETC.

The primary goal was to create bids for bonds that seemed ludicrously cheap. At this time, many bonds were truly trading wide because of liquidity concerns rather than solvency concerns. Basis trades were blowing apart, any day, you ran the risk that the HY bond you had would TRACE 10 points lower than the last trade because someone had to sell. These programs worked, but they also helped banks. Reducing credit spreads helped their existing balance sheets, and it made it easier to sell assets in efforts to clean up their balance sheets. Ultimately, by 2009, enough had been done that markets turned the corner and normalized.

Tacit Complicity

The Fed, and Treasury, and FDIC were doing so much to help banks get cheap funding, that it must have been horribly frustrated with confronting elevated LIBOR every single day. No matter what they did, LIBOR remained stubbornly high, and the banks with the highest submission rates would be at risk of yet another “bear raid”. Is it possible, maybe even probable, that the regulators would look away and ignore signs that “elevated” LIBOR wasn’t as elevated as it should be. Were they happy to see evidence that their programs were “working” and decided that is why some LIBOR rates seemed lower than some people thought they should be? Clearly Barclay’s thought other banks were submitting rates that were too low.

If LIBOR was coming down, markets were calmer because of it, would you really question it? Would you go and tell people to submit proper rates, knowing that would send another shockwave through the system, making your job harder?

We don’t yet know what went on, but I suspect anyone thinking that Barclay’s warnings that other banks were submitting LIBOR quotes that were too low, encouraged the Fed to take aggressive action to fix that, will be disappointed.

Fixing LIBOR

Since LIBOR is here to stay, there is a quick way to “fix” it. If the central banks want to control LIBOR and remove the “credit” element that is problematic for them, then they can make 2 quick and easy changes.

The BBA can change the question to “where is the best rate at which you can borrow on an unsecured basis”. The Fed (and other central banks) can then create a program where they will lend overnight, 1 week, 1 month, 3 months, and 6 months to banks. Those rates would then become a ceiling on LIBOR. LIBOR wouldn’t go above those rates posted by the Fed since the banks could borrow from the Fed and that would meet the criteria. I’m not sure the Fed can do unsecured lending, so maybe it needs to be tweaked further, but no reason it can be done.

Also, has anyone ever seen 4 month LIBOR used in a trade? Simplify the submissions. I think overnight, 1 week, 1 month, 3 month, and 6 month would be sufficient. Fewer points is likely to produce more accurate results because banks might actually try and determine the rates and input them. Seriously, if any submitting bank actually determines where 10 month LIBOR is rather than just interpolating it, I’d be shocked. Heck, on most days they probably just do a curve shift based on market tone rather than trying to figure out an actual rate. But let’s limit LIBOR to ones that are actually used. Maybe I’m wrong and 4 month LIBOR is used all the time, but somehow I think not.